pwn.college: Assembly Refreasher

模板

1 | |

Level 6

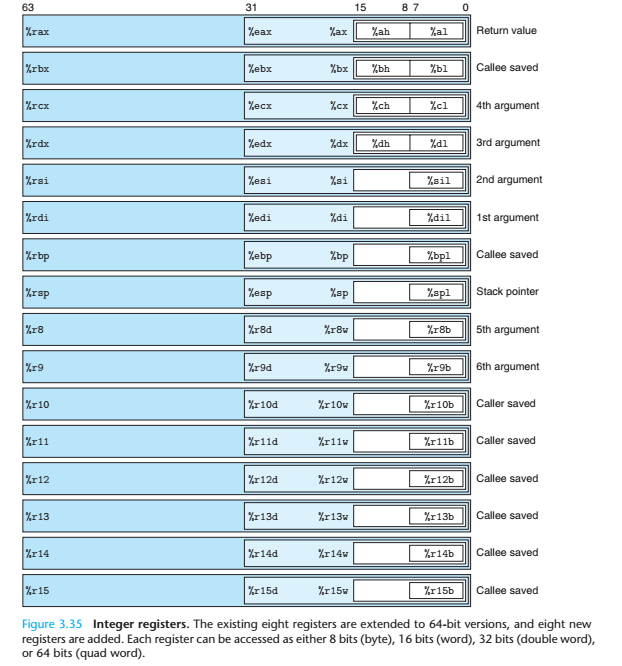

Another cool concept in x86 is the independent access to lower register bytes.

Each register in x86 is 64 bits in size, in the previous levels we have accessed

the full register using rax, rdi or rsi. We can also access the lower bytes of

each register using different register names. For example the lower

32 bits of rax can be accessed using eax, lower 16 bits using ax,

lower 8 bits using al, etc.

MSB LSB

+—————————————-+

| rax |

+——————–+——————-+

| eax |

+———+———+

| ax |

+—-+—-+

| ah | al |

+—-+—-+

Lower register bytes access is applicable to all registers_use.

Using only the following instruction(s):

mov

Please compute the following:

rax = rdi modulo 256

rbx = rsi module 65536

mod256 就是低8位设置为0,mod 65535就是低16位设置为0

Level 7

In this level you will be working with bit logic and operations. This will involve heavy use of directly interacting with bits stored in a register or memory location. You will also likely need to make use of the logic instructions in x86: and, or, not, xor.

Shifting in assembly is another interesting concept! x86 allows you to ‘shift’

bits around in a register. Take for instance, rax. For the sake of this example

say rax only can store 8 bits (it normally stores 64). The value in rax is:

rax = 10001010

We if we shift the value once to the left:

shl rax, 1

The new value is:

rax = 00010100

As you can see, everything shifted to the left and the highest bit fell off and

a new 0 was added to the right side. You can use this to do special things to

the bits you care about. It also has the nice side affect of doing quick multiplication,

division, and possibly modulo.

Here are the important instructions:

shl reg1, reg2 <=> Shift reg1 left by the amount in reg2

shr reg1, reg2 <=> Shift reg1 right by the amount in reg2

Note: all ‘regX’ can be replaced by a constant or memory location

Using only the following instructions:

mov, shr, shl

Please perform the following:

Set rax to the 4th least significant byte of rdi

i.e.

rdi = | B7 | B6 | B5 | B4 | B3 | B2 | B1 | B0 |

Set rax to the value of B3

Code

1 | |

Level 8

In this level you will be working with bit logic and operations. This will involve heavy use of directly interacting with bits stored in a register or memory location. You will also likely need to make use of the logic instructions in x86: and, or, not, xor.

Bitwise logic in assembly is yet another interesting concept!

x86 allows you to perform logic operation bit by bit on registers.

For the sake of this example say registers only store 8 bits.

The values in rax and rbx are:

rax = 10101010

rbx = 00110011

If we were to perform a bitwise AND of rax and rbx using the “and rax, rbx” instruction

the result would be calculated by ANDing each pair bits 1 by 1 hence why

it’s called a bitwise logic. So from left to right:

1 AND 0 = 0, 0 AND 0 = 0, 1 AND 1 = 1, 0 AND 1 = 0 …

Finally we combine the results together to get:

rax = 00100010

Here are some truth tables for reference:

AND OR XOR

A | B | X A | B | X A | B | X

—+—+— —+—+— —+—+—

0 | 0 | 0 0 | 0 | 0 0 | 0 | 0

0 | 1 | 0 0 | 1 | 1 0 | 1 | 1

1 | 0 | 0 1 | 0 | 1 1 | 0 | 1

1 | 1 | 1 1 | 1 | 1 1 | 1 | 0

Without using the following instructions:

mov, xchg

Please perform the following:

rax = rdi AND rsi

i.e. Set rax to the value of (rdi AND rsi)

AND 指令在两个操作数的对应位之间进行(按位)逻辑与(AND)操作,并将结果存放在目标操作数中

1 | |

Level 9

In this level you will be working with bit logic and operations. This will involve heavy use of directly interacting with bits stored in a register or memory location. You will also likely need to make use of the logic instructions in x86: and, or, not, xor.

Using only following instructions:

and, or, xor

Implement the following logic:

if x is even then

y = 1

else

y = 0

where:

x = rdi

y = rax

Level 10

In this level you will be working with memory. This will require you to read or write

to things stored linearly in memory. If you are confused, go look at the linear

addressing module in ‘ike. You may also be asked to dereference things, possibly multiple

times, to things we dynamically put in memory for you use.

Up until now you have worked with registers as the only way for storing things, essentially

variables like ‘x’ in math. Recall that memory can be addressed. Each address contains something

at that location, like real addresses! As an example: the address ‘699 S Mill Ave, Tempe, AZ 85281’

maps to the ‘ASU Campus’. We would also say it points to ‘ASU Campus’. We can represent this like:

[‘699 S Mill Ave, Tempe, AZ 85281’] = ‘ASU Campus’

The address is special because it is unique. But that also does not mean other address cant point to

the same thing (as someone can have multiple houses). Memory is exactly the same! For instance,the address in memory that your code is stored (when we take it from you) is 0x400000.

In x86 we can access the thing at a memory location, called dereferencing, like so:

mov rax, [some_address] <=> Moves the thing at ‘some_address’ into rax

This also works with things in registers:

mov rax, [rdi] <=> Moves the thing stored at the address of what rdi holds to rax

This works the same for writing:

mov [rax], rdi <=> Moves rdi to the address of what rax holds.

So if rax was 0xdeadbeef, then rdi would get stored at the address 0xdeadbeef:

[0xdeadbeef] = rdi

Note: memory is linear, and in x86, it goes from 0 - 0xffffffffffffffff (yes, huge).

Please perform the following:

- Place the value stored at 0x404000 into rax

- Increment the value stored at the address 0x404000 by 0x1337

Make sure the value in rax is the original value stored at 0x404000 and make sure

that [0x404000] now has the incremented value.

1 | |

Level 11

In this level you will be working with memory. This will require you to read or write

to things stored linearly in memory. If you are confused, go look at the linear

addressing module in ‘ike. You may also be asked to dereference things, possibly multiple

times, to things we dynamically put in memory for you use.

Recall that registers in x86_64 are 64 bits wide, meaning they can store 64 bits in them.

Similarly, each memory location is 64 bits wide. We refer to something that is 64 bits

(8 bytes) as a quad word. Here is the breakdown of the names of memory sizes:

- Quad Word = 8 Bytes = 64 bits

- Double Word = 4 bytes = 32 bits

- Word = 2 bytes = 16 bits

- Byte = 1 byte = 8 bits

In x86_64, you can access each of these sizes when dereferencing an address, just like using

bigger or smaller register accesses:

mov al, [address] <=> moves the least significant byte from address to rax

mov ax, [address] <=> moves the least significant word from address to rax

mov eax, [address] <=> moves the least significant double word from address to rax

mov rax, [address] <=> moves the full quad word from address to rax

Remember that moving only into al for instance does not fully clear the upper bytes.

Please perform the following:

- Set rax to the byte at 0x404000

- Set rbx to the word at 0x404000

- Set rcx to the double word at 0x404000

- Set rdx to the quad word at 0x404000

1 | |

Level 12

In this level you will be working with memory. This will require you to read or write

to things stored linearly in memory. If you are confused, go look at the linear

addressing module in ‘ike. You may also be asked to dereference things, possibly multiple

times, to things we dynamically put in memory for you use.

It is worth noting, as you may have noticed, that values are stored in reverse order of how we

represent them. As an example, say:

[0x1330] = 0x00000000deadc0de

If you examined how it actually looked in memory, you would see:

[0x1330] = 0xde 0xc0 0xad 0xde 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00

This format of storing things in ‘reverse’ is intentional in x86, and its called Little Endian.

For this challenge we will give you two addresses created dynamically each run. The first address will be placed in rdi. The second will be placed in rsi.

Using the earlier mentioned info, perform the following:

- set [rdi] = 0xDEADBEEF00001337

- set [rsi] = 0x000000C0FFEE0000

Hint: it may require some tricks to assign a big constant to a dereferenced register. Try setting a register to the constant than assigning that register to the derefed register.

1 | |

Level 13

In this level you will be working with memory. This will require you to read or write

to things stored linearly in memory. If you are confused, go look at the linear

addressing module in ‘ike. You may also be asked to dereference things, possibly multiple

times, to things we dynamically put in memory for you use.

Recall that memory is stored linearly. What does that mean? Say we access the quad word at 0x1337:

[0x1337] = 0x00000000deadbeef The real way memory is layed out is byte by byte, little endian:

[0x1337] = 0xef

[0x1337 + 1] = 0xbe

[0x1337 + 2] = 0xad

…

[0x1337 + 7] = 0x00

What does this do for us? Well, it means that we can access things next to each other using offsets,

like what was shown above. Say you want the 5th byte from an address, you can access it like:

mov al, [address+4]

Remember, offsets start at 0.

Preform the following:

- load two consecutive quad words from the address stored in rdi

- calculate the sum of the previous steps quad words.

- store the sum at the address in rsi

1 | |

Level 14

In this level you will be working with the Stack, the memory region that dynamically expands and shrinks. You will be required to read and write to the Stack, which may require you to use the pop & push instructions. You may also need to utilize rsp to know where the stack is pointing.

In these levels we are going to introduce the stack.

The stack is a region of memory, that can store values for later.

To store a value a on the stack we use the push instruction, and to retrieve a value we use pop.

The stack is a last in first out (LIFO) memory structure this means

the last value pushed in the first value popped.

Imagine unloading plates from the dishwasher let’s say there are 1 red, 1 green, and 1 blue.

First we place the red one in the cabinet, then the green on top of the red, then the blue.

Out stack of plates would look like:

Top —-> Blue

Green

Bottom -> Red

Now if wanted a plate to make a sandwhich we would retrive the top plate from the stack

which would be the blue one that was last into the cabinet, ergo the first one out.

Subtract rdi from the top value on the stack.

1 | |

Level 15

In this level you will be working with the Stack, the memory region that dynamically expands and shrinks. You will be required to read and write to the Stack, which may require you to use the pop & push instructions. You may also need to utilize rsp to know where the stack is pointing.

In this level we are going to explore the last in first out (LIFO) property of the stack.

Using only following instructions:

push, pop

Swap values in rdi and rsi.

i.e.

If to start rdi = 2 and rsi = 5

Then to end rdi = 5 and rsi = 2

1 | |

Level 16

In the previous levels you used push and pop to store and load data from the stack

however you can also access the stack directly using the stack pointer.

The stack pointer is stored in the special register “rsp”.

rsp always stores the memory address to the top of the stack,

i.e. the memory address of the last value pushed.

Similar to the memory levels we can use [rsp] to access the value at the memory address in rsp.

Without using pop please calculate the average of 4 consecutive quad words stored on the stack.

Store the average on the top of the stack. Hint:

RSP+0x?? Quad Word A

RSP+0x?? Quad Word B

RSP+0x?? Quad Word C

RSP Quad Word D

RSP-0x?? Average

1 | |

Level 17

In this level you will be working with control flow manipulation. This involves using instructions

to both indirectly and directly control the special register rip, the instruction pointer.

You will use instructions like: jmp, call, cmp, and the like to implement requests behavior.

Earlier, you learned how to manipulate data in a pseudo-control way, but x86 gives us actual

instructions to manipulate control flow directly. There are two major ways to manipulate control

flow: 1. through a jump; 2. through a call. In this level, you will work with jumps. There are two types of jumps:

- Unconditional jumps

- Conditional jumps

Unconditional jumps always trigger and are not based on the results of earlier instructions.

As you know, memory locations can store data and instructions. You code will be stored at 0x40008c (this will change each run).

For all jumps, there are three types: - Relative jumps

- Absolute jumps

- Indirect jumps

In this level we will ask you to do both a relative jump and an absolute jump. You will do a relative jump first, then an absolute one. You will need to fill space in your code with something to make this relative jump possible. We suggest using the nop instruction. It’s 1 byte and very predictable.

Useful instructions for this level is:

jmp (reg1 | addr | offset) ; nop

Hint: for the relative jump, lookup how to use labels in x86.

Using the above knowledge, perform the following:

Create a two jump trampoline:

- Make the first instruction in your code a jmp

- Make that jmp a relative jump to 0x51 bytes from its current position

- At 0x51 write the following code:

- Place the top value on the stack into register rdi

- jmp to the absolute address 0x403000

https://www.developerastrid.com/assembly/assembly-language-program-transfer-instruction/

1 | |

Level 18

We will be testing your code multiple times in this level with dynamic values! This means we will be running your code in a variety of random ways to verify that the logic is robust enough to survive normal use. You can consider this as normal dynamic value se

We will now introduce you to conditional jumps–one of the most valuable instructions in x86.

In higher level programming languages, an if-else structure exists to do things like:

if x is even:

is_even = 1

else:

is_even = 0

This should look familiar, since its implementable in only bit-logic. In these structures, we can control the programs control flow based on dynamic values provided to the program. Implementing the above logic with jmps can be done like so:

1 | |

Often though, you want more than just a single ‘if-else’. Sometimes you want two if checks, followed by an else. To do this, you need to make sure that you have control flow that ‘falls-through’ to the next if after it fails. All must jump to the same done after execution to avoid the else.

There are many jump types in x86, it will help to learn how they can be used. Nearly all of them rely on something called the ZF, the Zero Flag. The ZF is set to 1 when a cmp is equal. 0 otherwise.

Using the above knowledge, implement the following:

if [x] is 0x7f454c46:

y = [x+4] + [x+8] + [x+12]

else if [x] is 0x00005A4D:

y = [x+4] - [x+8] - [x+12]

else:

y = [x+4] * [x+8] * [x+12]

where:

x = rdi, y = rax. Assume each dereferenced value is a signed dword. This means the values can start as a negative value at each memory position.

A valid solution will use the following at least once:

jmp (any variant), cmp

1 | |

Level 19

We will be testing your code multiple times in this level with dynamic values! This means we will be running your code in a variety of random ways to verify that the logic is robust enough to survive normal use. You can consider this as normal dynamic value se

The last set of jump types is the indirect jump, which is often used for switch statements in the real world. Switch statements are a special case of if-statements that use only numbers to determine where the control flow will go. Here is an example:

switch(number):

0: jmp do_thing_0

1: jmp do_thing_1

2: jmp do_thing_2

default: jmp do_default_thing

The switch in this example is working on number, which can either be 0, 1, or 2. In the case that number is not one of those numbers, default triggers. You can consider this a reduced else-if type structure.

In x86, you are already used to using numbers, so it should be no suprise that you can make if statements based on something being an exact number. In addition, if you know the range of the numbers, a switch statement works very well. Take for instance the existence of a jump table. A jump table is a contiguous section of memory that holds addresses of places to jump. In the above example, the jump table could look like:

[0x1337] = address of do_thing_0

[0x1337+0x8] = address of do_thing_1

[0x1337+0x10] = address of do_thing_2

[0x1337+0x18] = address of do_default_thing

Using the jump table, we can greatly reduce the amount of cmps we use. Now all we need to check is if number is greater than 2. If it is, always do:

jmp [0x1337+0x18]

Otherwise:

jmp [jump_table_address + number * 8]

Using the above knowledge, implement the following logic:

if rdi is 0:

jmp 0x403026

else if rdi is 1:

jmp 0x403086

else if rdi is 2:

jmp 0x4030d8

else if rdi is 3:

jmp 0x4030f3

else:

jmp 0x403133

Please do the above with the following constraints:

- assume rdi will NOT be negative

- use no more than 1 cmp instruction

- use no more than 3 jumps (of any variant)

- we will provide you with the number to ‘switch’ on in rdi.

- we will provide you with a jump table base address in rsi.

1 | |

Level 20

In a previous level you computed the average of 4 integer quad words, which

was a fixed amount of things to compute, but how do you work with sizes you get when

the program is running? In most programming languages a structure exists called the

for-loop, which allows you to do a set of instructions for a bounded amount of times.

The bounded amount can be either known before or during the programs run, during meaning

the value is given to you dynamically. As an example, a for-loop can be used to compute

the sum of the numbers 1 to n:

sum = 0

i = 1

for i <= n:

sum += i

i += 1

Please compute the average of n consecutive quad words, where:

rdi = memory address of the 1st quad word

rsi = n (amount to loop for)

rax = average computed

1 | |

Level 21

In previous levels you discovered the for-loop to iterate for a number of times, both dynamically and statically known, but what happens when you want to iterate until you meet a condition? A second loop structure exists called the while-loop to fill this demand. In the while-loop you iterate until a condition is met. As an example, say we had a location in memory with adjacent numbers and we wanted to get the average of all the numbers until we find one bigger or equal to 0xff:

average = 0

i = 0

while x[i] < 0xff:

average += x[i]

i += 1

average /= i

Using the above knowledge, please perform the following:

Count the consecutive non-zero bytes in a contiguous region of memory, where:

rdi = memory address of the 1st byte

rax = number of consecutive non-zero bytes

Additionally, if rdi = 0, then set rax = 0 (we will check)!

An example test-case, let:

rdi = 0x1000

[0x1000] = 0x41

[0x1001] = 0x42

[0x1002] = 0x43

[0x1003] = 0x00

then: rax = 3 should be set

We will now run multiple tests on your code, here is an example run:

- (data) [0x404000] = {10 random bytes},

- rdi = 0x404000

1 | |

Level 22

In previous levels you implemented a while loop to count the number of consecutive non-zero bytes in a contiguous region of memory. In this level you will be provided with a contiguous region of memory again and will loop over each performing a conditional operation till a zero byte is reached.

All of which will be contained in a function!

A function is a callable segment of code that does not destory control flow.

Functions use the instructions “call” and “ret”.

The “call” instruction pushes the memory address of the next instruction onto

the stack and then jumps to the value stored in the first argument.

Let’s use the following instructions as an example:

0x1021 mov rax, 0x400000

0x1028 call rax

0x102a mov [rsi], rax

- call pushes 0x102a, the address of the next instruction, onto the stack.

- call jumps to 0x400000, the value stored in rax.

The “ret” instruction is the opposite of “call”. ret pops the top value off of

the stack and jumps to it.

Let’s use the following instructions and stack as an example:

Stack ADDR VALUE

0x103f mov rax, rdx RSP + 0x8 0xdeadbeef

0x1042 ret RSP + 0x0 0x0000102a

ret will jump to 0x102a

Please implement the following logic:

str_lower(src_addr):

rax = 0

if src_addr != 0:

while [src_addr] != 0x0:

if [src_addr] <= 90:

[src_addr] = foo([src_addr])

rax += 1

src_addr += 1

foo is provided at 0x403000. foo takes a single argument as a value

We will now run multiple tests on your code, here is an example run:

- (data) [0x404000] = {10 random bytes},

- rdi = 0x404000

1 | |

Level 23

In the previous level, you learned how to make your first function and how to call other functions. Now we will work with functions that have a function stack frame. A function stack frame is a set of pointers and values pushed onto the stack to save things for later use and allocate space on the stack for function variables.

First, let’s talk about the special register rbp, the Stack Base Pointer. The rbp register is used to tell where our stack frame first started. As an example, say we want to construct some list (a contiguous space of memory) that is only used in our function. The list is 5 elements long, each element is a dword.

A list of 5 elements would already take 5 registers, so instead, we can make pace on the stack! The assembly would look like:

1 | |

Notice how rbp is always used to restore the stack to where it originally was. If we don’t restore the stack after use, we will eventually run out TM. In addition, notice how we subtracted from rsp since the stack grows down. To make it have more space, we subtract the space we need. The ret and call still works the same. It is assumed that you will never pass a stack address across functions, since, as you can see from the above use, the stack can be overwritten by anyone at any time.

Once, again, please make function(s) that implements the following:

most_common_byte(src_addr, size):

b = 0

i = 0

for i <= size-1:

curr_byte = [src_addr + i]

[stack_base - curr_byte] += 1

b = 0

1 | |

Assumptions:

- There will never be more than 0xffff of any byte

- The size will never be longer than 0xffff

- The list will have at least one element

Constraints:

- You must put the “counting list” on the stack

- You must restore the stack like in a normal function

- You cannot modify the data at src_addr

1 | |